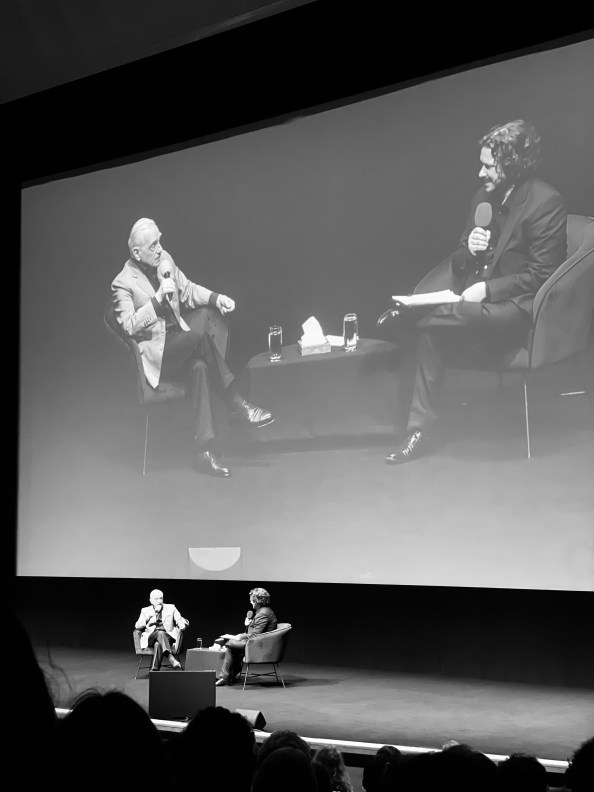

He’s been around a long time. But he isn’t closed minded. Martin Scorsese addressed the Festival Hall at London’s Southbank this weekend to discuss not just his latest film, but his latest state of the union on ‘grown up films,’ where cinema is going and why he thinks content is ‘nothing more than candy.’

What’s great about Scorsese is he gives context, and his context of growing up in a post War era on Manhattan’s lower east side is so rich and in direct alignment with an historical revolution in cinema history it’s spellbinding. As a child with asthma he was relegated to the proverbial ‘safe spaces’ in his neighbourhood: his bedroom, or the movie theatre down the street. The doctors orders therefore, not only resulted in well-ventilated areas, but a strict diet of the best movies that cinema had to offer on TV and in the theatres in the fifties. Scorsese stressed the relative lack of knowledge everyone had about his would-be craft at the time, he simply stumbled across powerhouse performances and European auteurs rather than being told to watch them. “It wasn’t like an ‘eat your spinach type of thing.’ No one told me: this is an important film to watch.’ He admits that the environment he grew up in, that is in a rough and tumble neighbourhood, wasn’t necessarily conducive or tolerant of a quiet, budding artist. “Let’s just say I had to draw frames for my pictures away from all that. I had to do it privately.”

An acquaintance in his neighbourhood who thrived around others with that type of rougher lifestyle that would characterise some of his later films was none other than a young Bobby De Niro. At a party one evening, De Niro spotted Scorsese as a kid he know from down the street and they bonded instantly. That bond has spanned 7 decades and is one of the most recognisable actor-director collaborations. The first chapter in that story started with the incomparable Mean Streets which Scorsese termed ‘a provincial film.’ His upbringing essentially drove the genesis of this film, with all roads leading to the meanest of streets. De Niro is the charming chancer, and Harvey Keitel is brilliant as the cool headed diplomat. It was authentic, these lads knew characters just like this from the streets. Scorsese fought tooth and nail with the studio to have it filmed on location in New York, while they wanted to film it in LA to cut costs. ‘It’s a quintessential New York movie. Even the alley ways in LA were too clean.’ He later recalled how he was ‘kicked out’ of LA in later years. I think that’s a nice way of saying that his heart always veers East.

The conversation turned slightly darker as it always does when Taxi Driver was mentioned. An astonishing film punctuated by Bernard Herrmann’s tempered score, I am equally haunted and enthralled by it since first seeing it when I was seventeen. Nothing prepares you for Bickle’s slow descent into madness, his venom and vitriol for the establishment and the New York City sewer he lived in is plastered across every frame. Scorsese in his most vulnerable moment on stage revealed that this film was a vessel for him to funnel his own rage into. His soft and artistic demeanour never quite gelled with life on the streets and that inability to defend himself physically was seen illuminated in Travis Bickle’s lucid yellow Manhattan cab. ‘The guys who used force generally won. I could never do that. It was only later I found out using your mind was more powerful.’

Moderator Edgar Wright asked why Scorsese has been essentially the last guard holding up ‘grown up cinema’ alluding to the filmmaker constantly being draw into the foray to comment on the ridiculousness of the Marvel phenomenon. ‘I didn’t want to be the last guard. In truth I don’t know where cinema is going.‘ But he knows stories are important and big screens are historically the best way to get them across. Other formats will prevail, people will consume media in fragmented ways but he’s defiant in that it wont replace real cinema. ‘Content isn’t art. Content is like candy,’ he said in closing.

Chew on that.