In its infancy, the Academy Awards operated initially with a jury. Silent star Mary Pickford was vying for an award in her first ‘talky’ with Coquette and had the five-strong jury over for tea to her lavish and sprawling estate, Pickfair Mansions where she lived with her filmmaker husband Douglas Fairbanks – unsurprisingly she won that year. Some awards ceremonies still exist, such as BAFTA where an unoptimised winner can emerge as a result of a vote arrived at by compromise. To avoid such blatant politicking and wining and dining, the jury was disbanded and replaced with an expansive voting base.

From the moment when the voting base was established, a new form of canvassing had to emerge and that created the modern Oscar campaign pedalled by specialist Oscar strategists. Today Oscar strategists must sway individual voters of a 10,000 strong body rather than a five person jury. Just a few weeks ago Emilia Perez was on track for a Best Picture win following a massive campaign bought by Netflix to clinch their first Oscar. A series of tweets found by a journalist derailed a carefully constructed campaign, halting its momentum as the international voter base could see the effects of this within minutes.

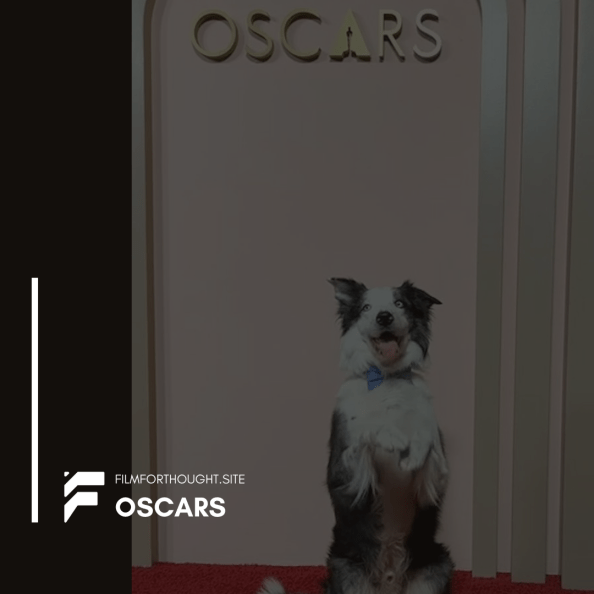

When momentum is already there however, subtle PR tactics are the modern way of grabbing attention. At last year’s Oscar ceremony, challenger distributor Neon brought the dog Messi to the Governor’s Luncheon on 12th February 2024, just shy of a month before the final awards ceremony. It proved to be an essential PR move in generating buzz about Anatomy of a Fall. Such was Messi’s popularity at the luncheon in which he outshined his human counterparts, the canine was not allowed to attend the actual Oscars ceremony as other distributors pointed out some petty technicalities, claiming that the presence of the dog would be an unfair advantage, especially as, being a dog, Messi was not an Academy nominee. The Hollywood Reporter’s Mikey O’Connell summarised ‘even a man’s best friend isn’t safe from politicking and petty grievances,’ that are of course endemic in the Oscar campaigning world. Oscar strategists have to be smart about how they get the attention of the international voting body, so various new tactics are deployed.

Oscar marketing campaigns form part of a long tradition and even as far back as 1943, the Hollywood columnist Edith Gwynn suggested that an Oscar be given out ‘for the best “we want an Oscar” publicity campaign.’ These days however modern Oscar campaigners’ challenge now is to adapt to the modern era, to be more subtle but bullish in their approach and to contend with such inputs like social media, communications and influencers to roll out the smartest campaign that is reflective of their film. A lot has changed, but a lot has stayed the same – they just now must adequately persuade a ten thousand strong garden tea party.