Blue Velvet is a personal favourite of Film For Thought, the seedy underbelly of white picket fence America has never been so vibrantly and violently portrayed on the screen. For its director David Lynch, this film kicked off a life-long career of working with Kyle McLachlan and Laura Dern, his vessels and collaborators for funnelling his art through. After the passing of such a renowned figure like Lynch earlier this year, there is a moment in which their art is seen in a new light and they are catapulted into legendary status. I watched the classic this month with an audience in a sold out screening at the Prince Charles cinema in London, and here’s my review of Blue Velvet in a few new lights; ten years after I saw the original and after its director has transformed in to legendary status.

There are a few films I watched when I was seventeen that have frozen in time, Taxi Driver, The Breakfast Club, On the Waterfront and Blue Velvet. You watch it the first time, and then you try not to watch them again for a while, with the fear that you’ll see a flaw that you were blinded by the first time. It became quite clear while watching Blue Velvet on the big screen as a now legitimate adult, I realised that the actual plot in the film must have been completely irrelevant to me when I first watched it. It makes sense therefore that that the idea for the film came to Lynch ‘as a feeling,’ rather than a preconceived story. He knew he wanted a severed ear in it, and he knew he wanted the accompanying haunting score Blue Velvet by Bobby Vinton – sometimes a disconnected set of inputs is all you need.

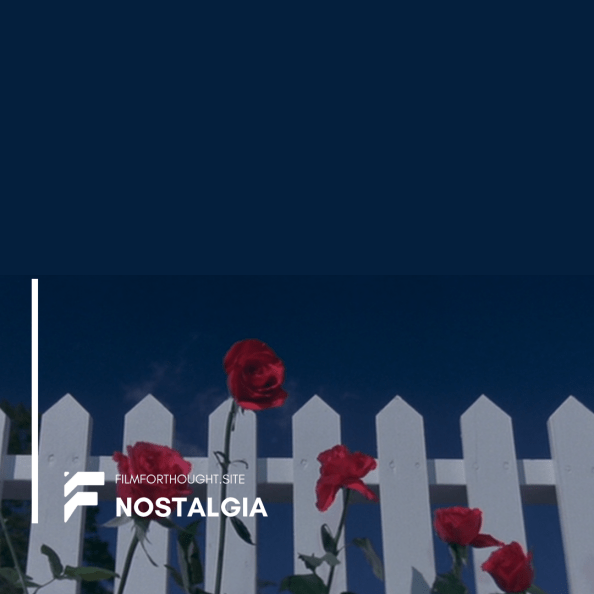

The setting for a film that had such a haunting premise is part of the magic of course. White picket fences and prim and proper rose bushes lining the streets are all necessary in setting up the perfect world so that we can explore its dark and imperfect seedy underbelly. Kyle McLachlan is our way into the world, a do-gooder and golden boy, forced to return home to the suburbs from his studies at college to look after his dad’s hardware shop while he’s in the hospital. In college, he is straddling two worlds between school and real life and this transition period is reflected in this film. Dressed to impress in oversized suits and shirts, he gives the illusion that he has his life together but in reality, he is a child dressed up as an adult. When he gets wind of a suspicious woman linked to a severed human ear he finds in the weeds while on a walk, he starts an amateur sleuthing operation, a curious kid that is about to bite off more than he can chew.

There is an ersatz feeling to all the characters, including Kyle McLachlan. There is something curiously odd about each person, each line and the manner in which they say it that can’t be specified. In the vein of noticing aspects here that I didn’t notice when I was younger, is how clever the set up is. The seedy exploration of the suburban underbelly comes in the guise of 1980s filmmaking. The cliched 80s sentiment could just as easy be in a John Hughes movie, and it’s evident now that everything has to be so cringe and light, in order to make the darkness so deep. This was none more evident when with an audience in the Prince Charles, cliched, Lynchian lines that got roaring laughs, including when Kyle McLachlan says he has a human ear in a bag and the detective plainly states, ‘that’s a human ear alright.’ At one point, a person laughed so wholeheartedly that someone at the back shouted “it’s not a comedy!” – and at that moment David Lynch was probably looking down and laughing at both of them. The interspersing of suburban America and the dark underbelly in itself is so at odds, that when the worlds collide, the result is pure bizarreness that people will react to in different ways.

The severed ear sets in motion a chain of events that sets McLachlan off on a path of discovery, of himself and the world he thought he knew. Lynch said it was an ear because he knew it needed to be a body part with an opening, the ear appears with mould on it, and the camera follows within to show that the underbelly of middle America is, beneath it all, rotten to the core. McLachlan uncovers Dorothy Valens, a woman stuck in a situation where her husband and son are used as pawns in a sick game to placate Dennis Hopper’s character. It’s easy for McLachlan to observe all of this at a distance, to want to help Dorothy in theory and that his curious nose will be used for good. But in doing all this his character brushes up with his dark side. It makes you question if life can really be viewed at from a distance, and questions if you can be unwillingly led astray by proximity. Or the most frightening question of all, if you have seen it, and you understand it, is it now in you too?

Like the recent Zone of Interest film about the family who live on the outskirts of Aushwitz, the director Johnathan Glazer said his tonally offbeat interstitials of a girl leaving apples in the camp at night were essential in creating the movie, because without that small glimmer of light and hope, the paralysis of evil would be too overpowering. In the same vein, Lynch needed the ethereal Laura Dern to fill this role. Her beautiful voice and lightness acts as the movie’s hope. Her surreal monologue of good overcoming evil at the halfway point comes to pass at the end as the robin eats a worm as a signifier for overcoming the badness in the world. That’s what I took from it anyway. The great thing is that Lynch is now in that legendary branch of directors where we can now interpret for the rest of our days.

The Prince Charles is showing Blue Velvet multiple times over the next few weeks

https://princecharlescinema.com/film/2666249/blue-velvet/